|

THE SECRETS BURIED AT LEXINGTON GREEN

WHO REALLY FIRED “THE SHOT HEARD ROUND THE WORLD”?

By James Perloff

Xxx

I grew up mostly in Lexington, Mass., where the famed “shot heard round the world” was fired. On my way home

from high school each day, I would pass Lexington Green, where colonial militia had assembled on the morning

of April 19, 1775, and encountered a force of British redcoats who were on their way to neighboring Concord to

confiscate armaments. Shots rang out; eight militia men died; nine were wounded; the Revolutionary War had begun.

The redcoats suffered only one minor wound and continued to Concord, where they found fewer munitions than

expected. They spent the rest of the day being routed by superior numbers of militia, on a long and bloody retreat

back to their garrison in the city of Boston.

As I walked home, I would pass still-standing Buckman’s Tavern, where the militia had assembled before the

battle; and continuing my trek up Hancock Street, would pass the Hancock-Clarke House, another historic site.

It was here that Samuel Adams and John Hancock— leaders of the revolution in Massachusetts—had been staying the

night before the battle. Paul Revere stopped there to see them on his famous “Midnight Ride.”

These historic matters were hardly on my mind at the time. However many years later, having written widely on

political affairs, I took my son on a tour of historic Lexington at his request, and questions began troubling me.

Who fired the first shot has been controversial for over two centuries. Was it the British or Americans? Each

side accused the other.

A patriotic friend of mine, who publicly lectures on the battle in a tricorn hat, told me, “Jim, the Americans

would never have fired first. You’ve got 80 militia facing 700 British regulars. It would have been suicidal.”

“I see your point,” I said, “but it also seems to me that British troops, under tight discipline, would not

have fired without provocation. It’s not like they were on a mission to start battles that day.”

So who did fire the “shot heard round the world”? The answer is important, because that shot ignited the American

Revolution, which in turned engendered the world’s most powerful nation. I believe the answer was a dark secret,

buried with the dead that April morning.

The Amazing Changing Lexington Portrayals

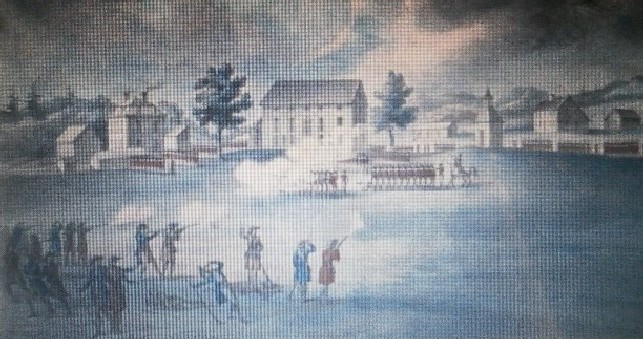

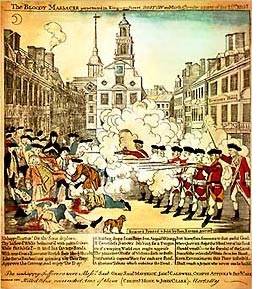

I direct the reader to the battle’s first artistic depiction, the engraving rendered by Amos Doolittle in the fall

of 1775, just a few months after the event.

Note that all the militia men are retreating or casualties.

Not one colonist is firing his gun or even loading.

Next we have the lithograph produced by William S. Pendleton in about 1830:

While a number of militia men are retreating, some are now shooting.

Next comes Hammatt Billings’s rendering of 1868:

Here very few men retreat; most are engaged.

And finally we have “The Dawn of Liberty,” painted by Henry Sandham in 1886:

Every man is now standing his ground.

Note the transition from Picture 1 to Picture 4—from 100 percent retreat to 100

percent defiance. The credit for discovering this revealing sequence goes not to me, but to historian Harold Murdock,

who expounded on it nearly a century ago. While the casual observer might dismiss these changes as artistic license or

patriotic pride, the truth about Lexington’s “Picture of Dorian Gray” runs much deeper.

Doolittle’s 1775 picture very accurately represented how Massachusetts rebels wanted the event portrayed at that time.

Here is how the newspaper Massachusetts Spy reported it in an article widely reprinted throughout the colonies:

|

Americans! forever bear in mind the BATTLE of LEXINGTON! where British Troops, unmolested and unprovoked wantonly,

and in a most inhuman manner fired upon and killed a number of our countrymen….It is noticed they fired upon our people

as they were dispersing, agreeable to their command, and that we did not even return the fire. Eight of our men were

killed and nine wounded; The troops then laughed, and damned the Yankees.

|

As you can see, the article denied that the militia fired any shots. This accords with the official report authorized

by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress,

A Narrative, of the Excursion and

Ravages of the King's Troops. It contained

the depositions of many Lexington militiamen. All stated the king’s troops began firing on them. Not one deponent

expressly admitted to firing a shot, even in retaliation, though they did not deny firing retaliatory shots.

It also agrees with the account by William Heath, the brigadier general who took overall command of the militias as

they pursued the redcoats back to Boston. In his postwar

memoirs,

Heath described the British shooting at the Lexington

militia, but made no mention of return fire.1

So what changed perception of the event? In 1824, as the revolution’s 50th anniversary was approaching, politician Samuel

Hoar was giving a public address in Concord. The aging Marquis de Lafayette (who had been a general in the Revolution)

was there; Hoar told him he was standing where “the first forcible resistance” to the British occurred. Concord residents

affirmed that their town should be credited with firing, as Ralph Waldo Emerson would later put it, “the shot heard round

the world.” After all, nothing on the official record indicated the Lexington militia had discharged even one round.

This prompted outrage in Lexington, whose denizens insisted the honor belonged to them. And to prove their case, they

obtained depositions from 10 aged veterans and witnesses of the battle on Lexington Green. In a stunning variance from

the original sworn statements, all deponents now vigorously insisted that the militia fired upon the British, though

still claiming the redcoats began hostilities.

This inter-town debate raged for years, and was said to be symbolized in our annual Thanksgiving Day football game,

played between Lexington and Concord high schools. Virtually all historians today concede that the Lexington militia

fired; the controversy now is over who fired first. The Americans said it was the British; the British said the Americans.

Americans or British?

Though it may offend some U.S. patriots, I agree with

Derek W. Beck, American author of the

forthcoming book 1775, who concedes that the British reports were more credible. Why?

• The British freely admitted shooting first at the subsequent battle of Concord. Why would they tell the truth about

Concord, but lie about Lexington?

• British soldiers said the Americans fired first in their personal diaries, which were not intended for publication.

Why would the British lie to themselves in their diaries?

• As we have seen, in 1825 the Lexington militiamen amended the story given in their original 1775 depositions. This

shows they were guided by political exigencies of the day, weakening their credibility.

But why would a militia force commence hostilities when outnumbered ten to one? The solution to this mystery requires

understanding the historical context.

Freemasonry

Freemasonry deserves at least mention. In the late 18th century, two bloody anti-royalist revolutions erupted. One,

of course, was the French revolution. Few would deny Freemasonry played a major role in it. This was not only

documented by contemporary critics such as Augustin Barruel in

Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinsm (1797)

and John Robison in

Proofs of a Conspiracy (1798), but by Bonnet,

orator of the Convent of the Grand Orient Lodge of France, who later declared:

|

During the 18th century the glorious line of the Encyclopedistes found in our temples a fervent audience, which,

alone at that period, invoked the radiant motto, still unknown to the people, of “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.”

The revolutionary seed germinated rapidly in that select company. Our illustrious brother masons d’Alembert, Diderot,

Helvetius, d’Holbach, Voltaire and Condorcet, completed the evolution of people’s minds and prepared the way for a new

age. And when the Bastille fell, freemasonry had the supreme honor to present to humanity the charter which it had

friendly elaborated. . . .On August 25, 1789, the Constituent Assembly, of which more than 300 members were masons,

finally adopted, almost word for word, such as it had been for long elaborated in the lodges, the text of the immortal

declaration of the Rights of Man. At that decisive hour for civilization, French masonry was the universal conscience . . .

2

|

Of course, many have noted a distinction between Grand Orient Masonry, practiced on the European continent, and Scottish

Rite Masonry, practiced in Great Britain and North America, which they consider more benign. Nonetheless, it is difficult

to deny Freemasonic components to the American Revolution.

Paul Revere was dispatched on his famous ride from Boston by Joseph Warren. Warren also sent a second rider, William

Dawes, whom history has never glamorized like Revere. Revere and Dawes took different routes and both arrived at the

Lexington house where John Hancock was staying. What history books usually omit is that Joseph Warren was Grand Master

of St. Andrew’s Lodge in Boston; and that Revere, Dawes and Hancock were all members of that same Lodge. Thus the entire

circuit of Revere’s ride, from beginning to end, consisted of Freemasons bound to oaths of secrecy. So we could reasonably

ask if there was something to the ride beyond what history reports.

After the war, Revere became Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, which probably did not impair his subsequent

rise to historic glory.

Many other Freemasons were involved in the Revolution. Benjamin Franklin served not only as Grand Master of Pennsylvania,

but Grand Master of the Nine Sisters Lodge in Paris, as well belonging to Britain’s satanic Hellfire Club.

Nearly half the generals in the Continental Army were Freemasons—most famously, of course, George Washington, who was

later sworn in as President by Robert Livingston, Grand Master of New York’s Grand Lodge.

If you visit Lexington today, at the National Heritage Museum you will see a statue of George Washington donning his

Masonic apron. Not surprising, since the museum is run by Freemasons; its legal name is Scottish Rite Masonic Museum &

Library, Inc.

None of this imputes anything sinister to the vast majority of Freemasons in America today. But it is difficult to dismiss,

as coincidental, the influence of Freemasonry on these two revolutions that exploded just a few years apart on separate

continents.

Brewers of Revolution

But by far the most important insights into Lexington’s secrets derive from examining the two men who Paul Revere rode to

meet there—Samuel Adams and John Hancock.

When most Americans hear “Founding Fathers,” they typically think of Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Madison and Hamilton.

John Hancock is usually remembered only for his extra-large signature on the Declaration of Independence. If an Adams is

recalled, it is John Adams, second President of the United States, rather than his second cousin Sam, whom most Americans

today identify only as a figure on beer labels.

But Americans of the colonial era would be surprised to learn that Sam Adams has faded into semi-oblivion. Thomas Jefferson

said “he was truly the Man of the Revolution.” When he died, the Boston press called him “Father of the American Revolution.”

Indeed, the revolution was in many respects a “Massachusetts event” —here was the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party,

and the battle that began the war. Sam Adams was entangled in them all.

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), colonists and British troops had fought on the same side. Samuel Adams, who

biographer John Miller called “pioneer in propaganda,” was instrumental in abruptly changing Americans’ perception of

British soldiers from “good guys” to “bad guys.”

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), colonists and British troops had fought on the same side. Samuel Adams, who

biographer John Miller called “pioneer in propaganda,” was instrumental in abruptly changing Americans’ perception of

British soldiers from “good guys” to “bad guys.”

Britain’s national debt had nearly doubled by the long war’s end, and Parliament felt the burden of paying it off should

not be borne by British taxpayers alone, but by the colonists as well, especially since they were the main beneficiaries

of the war’s victorious outcome. The result was the Sugar Act of 1764, which placed a tax on molasses of three pennies

per gallon.

Sam Adams, a member of the Massachusetts state legislature, was the most outspoken opponent of the Act. Widely quoted

in newspapers and pamphlets, he declared:

"For if our Trade may be taxed, why not our Lands? Why not the Produce of our Lands & everything we possess or make use

of?... If Taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal Representation where they are laid, are we not

reduced from the Character of free Subjects to the miserable State of tributary Slaves?"

3

This established two patterns to Adams’s rhetoric: (1) amplify a perceived wrong well beyond its actual boundaries – i.e.,

if you gave the king a penny today, tomorrow he would demand a pound; (2) equate British taxation policies with images of

slavery.

The Sugar Act was repealed, but it was Britain’s next revenue measures—the Stamp Act of 1765 (repealed in 1766) and the

Townshend Acts of 1767— that catapulted Adams to power. (The Stamp Act would have placed tax on many documents, such as

contracts, licenses, diplomas and newspapers, each to require a revenue stamp; the Townshend Acts placed duties on various

imports from Britain.) These measures were protested throughout the colonies, but nowhere more violently than Boston.

As historian William H. Hallahan notes:

|

Samuel Adams was gathering and organizing a collection of waterfront mobs who were controlled by his lieutenant, Will

Molineaux, a draper; and on occasion even by Paul Revere. Henceforth, Boston was controlled by a “trained mob” glorified

by its title: the Sons of Liberty. Sam Adams was its keeper. Adams fashioned another powerful revolutionary tool when

he helped spread Sons of Liberty organizations elsewhere in the colonies, where they could be orchestrated into mobs for

demonstrations, intimidation, and street violence coordinated with events in Boston.4

|

Adams became Boston’s political boss, running the city in an early Tammany style. Even before town meetings took place,

Adams and his cronies would pre-select candidates at Adams’s private smoke-filled “Boston Caucus” room; votes were often

bought at the price of a few tavern drinks, and his thugs ensured control of town meetings at Boston’s Faneuil Hall.

During this rise, Adams recruited the most important ally of his political life: John Hancock.

During this rise, Adams recruited the most important ally of his political life: John Hancock.

Both men came from prosperous families. But while Sam Adams turned all his father’s businesses— including a malt house for

brewers—into ruins, Hancock became the wealthiest man in Massachusetts, primarily through smuggling

operations. A peerless fop, Hancock rode about in a gilded carriage he had specially built in England. Before the revolution

began, he even had tailors make him a collection of ornate military costumes he imagined he would wear as commander-in-chief

of the Continental Army. When this distinction instead went to George Washington, he bore a grudge that festered for years.

Although his extra-large signature on the Declaration of Independence has been popularly ascribed to courageous defiance,

it might also be seen as characteristic of his overbearing vanity.

Adams recruited Hancock to be financial angel of the revolution in Massachusetts. Playing to his ego, he allowed Hancock

to take the most publicly prominent positions, but there was no doubt that Adams, the back-room intriguer, was the

revolutionary mastermind. He soon brought political enemies to heel.

Andrew Oliver, who had been designated distributor of stamps in Boston, was hung in effigy by a mob, had his office vandalized

and his home stoned. Adams then forced him to publicly resign before a mob on Boston Common.

Adams learned that terror tactics could be employed to intimidate elected officials as well—by filling the legislature’s

gallery with hundreds of his “Mohawks” (Sons of Liberty) and posting the names of legislators considered Tories (British

loyalists) on Boston Common’s “Liberty Tree.”

John Mein, who began Boston’s first circulating library, ran an opposition newspaper called the Boston Chronicle.

While Adams was forcing Boston merchants to boycott British goods—at great loss to themselves—Mein published ships’

manifests proving that certain traders, including John Hancock, were secretly continuing profitable trade with Britain.

A mob then ransacked Mein’s office, and he was attacked on the street by twenty thugs armed with clubs and spades.

Orders were handed down for Mein’s arrest, and Sam Adams personally assisted in searching for him. Mein successfully

escaped the city, but freedom of the press departed with him.

Home after home of “Tories” were set upon by Adams’s mobs at night. Before undertaking their tasks, they would first

get “liquored up“ in Boston’s taverns (making it not inappropriate that Sam Adams is now immortalized on beer bottles).

Summoned by bells, whistles, and a horn, the mobs would pour out of the taverns, and descend on the houses of their

designated victims, first giving Mohawk “war whoops,” then terrorizing the families and ransacking their homes.

Looting became a “patriotic” act. Destroying the ledger books of creditors was not overlooked. Many loyalists were

stripped naked and made victims of the gruesome act of tarring and feathering.

But Adams went too far when he singled out Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Adams roused passions by falsely proclaiming the Stamp Act had been Hutchinson’s brainchild. This was a glaring

slander—the Massachusetts-born Hutchinson had opposed the Stamp Act. This mattered little to the drunken mob of some

500 that descended on the lieutenant governor’s house on the night of August 26, 1765. Hutchinson and his family barely

escaped with their lives. The mob set upon the house for the entire night, breaking the windows, destroying the walls

and furniture with axes, stealing all clothing, silverware and money, obliterating

Hutchinson’s library (which contained priceless books and manuscripts) and even pulling down the house’s cupola.

The specter of Hutchinson’s destroyed home sparked an outcry in Massachusetts—Deacon Timothy Pickering, Sr. of Salem

later compared the mob to the one that surrounded Lot’s house in the Bible. Throughout the colonies, shame fell on

Boston. As a result, Adams was forced to publicly criticize the incident, but he blamed it on “vagabond strangers.”

Eight of the perpetrators were arrested in Boston, but another mob simply broke into the jail and freed them. They

were never brought to trial.

Hutchinson minced no words about Sam Adams: “I doubt whether there is a greater Incendiary in the King’s dominions

or a man of greater malignity of heart, or who less scruples any measure ever so criminal to accomplish his purposes;

and I think I do him no injustice when I suppose he wishes the destruction of every Friend to Government in

America.”5

In the manner of Orwellian Newspeak, Sam Adams espoused “liberty” while destroying it; he denounced “tyranny” while

establishing it. Liberty is meaningless when granted only to people agreeing with those in power. Edward Bacon, the

state legislator from Barnstable, Mass.—where an elderly widow named

Abigail Freeman was tarred and feathered by a

gang of young thugs for expressing “Tory” opinions—said he preferred the master 3,000 miles away to the one in

Boston.6

By 1768, under Adams’s tutelage, Boston had become a bedlam of mob rule and violence. Freedom of speech, freedom of

the press, and justice were perishing. At this juncture, British troops were sent to Boston to restore order. One

Captain Evelyn would later write to his father, a clergyman in England: “Our arrival has in a great degree restored

that liberty they [loyalists] have been so long deprived of, even liberty of speech and security to their persons

and property, which has for years past been at the mercy of a most villainous mob.”7

Adams immediately sought to expel these troops. He began circulating to other colonies a “Journal of Events” which

alleged that British soldiers were regularly beating small boys and raping the city’s virtuous maidens. Adams did

not publish the “Journal” in Massachusetts, where its contents were known to be untrue; but other parts of the continent

were easy prey for his atrocity tales. Francis Bernard, governor of Massachusetts, said of Adams’s journal that, even

“if the Devil himself” had taken a hand, “there would not have been got together a greater collection of impudent

virulent & Seditious Lies, Perversions of Truth & Misrepresentations than are to be found in this

Publication.”8

In their own defense, the British soldiers said it would hardly be necessary to resort to rape in a city already so

teeming with women of easy virtue.

Adams’s Sons of Liberty began picking fights with redcoats in Boston taverns. One of the trademark quotes of Sam Adams’s

career was: “Put your enemy in the wrong, and keep him so, is a wise maxim in politics, as well as in war.” With this

principle in mind, Adams sought to generate a catalytic incident—one that would be prelude to Lexington Green.

Boston “Massacre”

On March 5, 1770, citizens of Boston found handbills posted around the city which read:

|

this is to inform ye Rebellious People in Boston, that ye Soldiers in ye 14th and 29th Regiments are determend to Joine

together and Defend themselves against all who Shall opose them

|

| Signed ye soldiers of ye 14th and 29th Regiments

|

If, in fact, the redcoats had planned violence against Boston’s citizens, it seems odd that they would broadcast their

intentions in advance. Nonetheless, the handbill was used to stir passions among Bostonians.

That evening, summoned by bells, a huge mob, many armed with clubs and staves, descended on King Street. They surrounded

the lone sentry on duty near the customs house, taunting him and pelting him with chunks of ice. The sentry called for

help. Captain Thomas Preston, officer of the watch at the nearby barracks, came to the sentry’s rescue with seven

soldiers. As the bells continued tolling, the crowd grew to some three or four hundred. They closed in on the nine

soldiers, pelting them with rocks, ice and snowballs, and daring them with chants of “Fire!” for they knew the redcoats

had orders not to shoot at citizens. As the crowd surrounded the soldiers, they began striking them, and hitting the

muzzles of their guns, with cudgels. One soldier, knocked to the ground by a blow from a club, and hearing the word

“Fire!” amid the chaos, jumped to his feet and shot at his assailants. Other soldiers fired as well. When it was over,

three of the mob lay dead; two were mortally wounded.

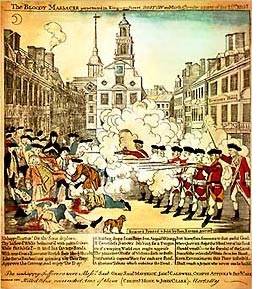

The next morning, Sam Adams delivered a fiery speech, and appointed himself and John Hancock heads of a committee that

demanded immediate removal of all British troops from Boston. Propaganda went full tilt. Adams’s lieutenant Paul Revere

swiftly produced a widely reproduced print of the “massacre” (five deaths being a somewhat hyperbolic use of that term).

It has been noted that Revere’s print included numerous

misrepresentations, the most distinct its depiction of the

shooting as an orderly volley, given on an officer’s command, suggesting it was a premeditated expression of official

British policy.

It has been noted that Revere’s print included numerous

misrepresentations, the most distinct its depiction of the

shooting as an orderly volley, given on an officer’s command, suggesting it was a premeditated expression of official

British policy.

Adams’s committee, which also included Joseph Warren and mob leader William Molineux, ordered publication of

A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston. It contained dozens of collected depositions, depicting the incident as

unprovoked wanton murder. Reading them, one is impressed that there was hardly a citizen of Boston who was not molested

by Captain Preston and his men that night. The depositions read as though written by a seedy playwright of maudlin

melodramas. Perhaps Adams had discovered that depositions, like votes and rioters, could be bought with a few tavern

drinks.

Two samples:

|

Deposition number 31:

I, Nathaniel Appleton, of lawful age, testify, that on Monday evening the 5th instant . . . I went to my front door

and saw several persons passing up and down the street, I asked what was the matter? was informed that the soldiers

at Murray's barrack were quarrelling with the inhabitants. Standing there a few minutes, I saw a number of soldiers,

about 12 or 15, as near as I could judge, come down from the southward, running towards the said barrack with drawn

cutlasses, and appeared to be passing by, but on seeing me in company with Deacon Marsh at my door, they turned out

of their course and rushed upon us with uplifted weapons, without our speaking or doing the least thing to provoke

them, with the utmost difficulty we escaped a stroke by retreating and closing the door upon them. I further declare,

that at that time my son, a lad about 12 years old, was abroad on an errand, and soon came home and told me that he

was met by a number of soldiers with cutlasses in their hands, one of which attempting to strike him, the child begg'd

for his life, saying, pray soldier save my life, on which the soldier reply'd, No damn you, I will kill you all,

and smote him with his cutlass, which glanced down along his arm and knocked him to the ground where they left him,

after the soldiers had all passed, the child arose and came home, having happily received no other damage than a

bruise on the arm.

Deposition No. 66:

I, John Wilson of lawful age testify, that on monday evening the 5th current, I… heard the bells ring and … I asked

what was the matter? The people said the soldiers had insulted the inhabitants … Then I came down King street opposite

the custom-house, and saw a man with a light color'd surtout coming from the main guard go up to the centry, and lay

his hand on his shoulder and speak some words to the centry, and then enter the custom-house door. On this the centry

grounded the breech of his gun, took out a cartridge, primed and loaded, and shoulder'd his firelock. After this I

drew back opposite Mr. Stone’s, & in a few minutes saw a party of soldiers headed by an officer coming down from the

main guard, crying to the inhabitants, Damn you, make way you boogers! I not moving from my place was struck by one

of them on the hip with the butt of his musquet, which bruised me so much that it was next day very sore, and much

discoloured. The officer seeing the soldier strike me said to the soldier in an angry manner why don't you prick the

boogers ? The party drew up before the custom-house door, and ranged to the west corner in a half circle, and charged

their pieces breast high. Some small boys coming up made a noise to the soldiers, on which the officer said to them why

don't you fire? Damn you, fire ! They hereupon fired, and two men fell dead in my

sight.9

|

These depositions portrayed the soldiers “Adams style” —cowards who beat children, who shot without provocation, their

conduct motivated by officers.

The soldiers were tried for murder, and Sam Adams expected that, with a jury stacked with his “Mohawks,” he would soon

see redcoats swinging from gallows on Boston Common. But the defense was led by Sam’s second cousin John—the future

President—who, despite threats against himself, did a creditable job. He saw to it that the jurors came from outside

Boston, and 38 witnesses testified that there had been a plot that night to attack the redcoats. The prosecution did

not even enter into evidence the threatening handbill alleged to have been written by the soldiers.

The most crushing blow for Sam Adams came with the deathbed confession of one of the two mortally wounded men—Patrick

Carr. Carr said the soldiers had been provoked into shooting; that they had shown far greater restraint than the

British soldiers Carr had seen facing mobs in his native Ireland; and he forgave the soldier who shot him, as he had

pulled the trigger in self-defense.

Outraged, Sam Adams publicly denounced Carr’s confession. Playing to the prejudices of the day, he said it should be

discounted because Carr was a “Papist.”10

The jury acquitted all but two of the soldiers, who were convicted of manslaughter. No redcoats swung from the gallows.

Sam’s cousin John—tactfully without naming names— remarked of the incident: “I suspected that this was the explosion

which had been intentionally wrought up by designing men who knew what they were aiming at, better than the instruments

employed.”11

The verdict stung Sam Adams, but taught him lessons that would prove useful. And he continued to play the massacre

for all it was worth. As the master of melodramatic propaganda, it is believed he had a great hand in writing John

Hancock’s torrid Boston Massacre fourth-anniversary

oration, of which here is a small sampling.

Bear in mind these words were being spoken more than three years after a Massachusetts jury rejected the murder charges

brought against the troops:

|

But I forbear, and come reluctantly to the transactions of that dismal night … when Satan, with his chosen band, opened

the sluices of New England's blood, and sacrilegiously polluted our land with the dead bodies of her guiltless sons! Let

this sad tale of death never be told without a tear…let every parent tell the shameful story to his listening children

until tears of pity glisten in their eyes, and boiling passions shake their tender frames…let all America join in one

common prayer to heaven that the inhuman, unprovoked murders of the fifth of March, 1770 … executed by the cruel hand

of Preston and his sanguinary coadjutors, may ever stand in history without a parallel… And though the murderers may

escape the just resentment of an enraged people; though drowsy justice …still nods upon her rotten seat….Ye dark

designing knaves, ye murderers, parricides! how dare you tread upon the earth which has drunk in the blood of slaughtered

innocents, shed by your wicked hands?

|

The Boston Tea Party

As it did with the Sugar Act, England had repealed the Stamp Act (from which it never collected one penny) in response

to colonial protests.

In 1766, Parliament, still seeking a practical means of raising revenues from the colonies, had summoned Benjamin Franklin,

the leading representative of American interests in Britain. The following exchange is of interest:

Q. What was the temper of America toward Great Britain before the year 1763?

A. The best in the world. They submitted willingly to the government of the Crown, and paid, in their courts, obedience

to acts of Parliament….

Q. Did you ever hear the authority of Parliament to make laws for America questioned till lately?

A. The authority of Parliament was allowed to be valid in all laws, except such as should lay internal taxes. It was

never disputed in laying duties to regulate commerce….

Q. Was it an opinion in America before 1763 that the Parliament had no right to lay taxes and duties there?

A. I never heard an objection to the right of laying duties to regulate commerce; but a right to lay internal taxes

was never supposed to be in Parliament, as we are not represented there…

Q. On what do you found your opinion that the people in America made any such distinction?

A. I know that whenever the subject has occurred in conversation where I have been present, it has appeared to be

the opinion of every one that we could not be taxed by a Parliament wherein we were not represented. But the payment

of duties laid by an act of Parliament as regulations of commerce was never disputed.12

|

Based on assurances, such as these from Franklin, that the colonies would respect Britain’s right to place duties on

her own commerce, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, assigning duties on various British goods sold in America.

Sam Adams then coerced Boston merchants to sign his “nonimportation agreement” on pain of being otherwise named a public

enemy and subject to mob violence (this had been prior to the arrival of the British troops). As we have seen, while

Boston merchants were going broke from the boycott, Adams looked the other way as his friend John Hancock continued

profitable trade with Britain—to borrow Orwell’s phrase, all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than

others.

In response to colonial protests, Parliament caved in—again. They removed duties on all goods except one—tea, via the

Tea Act of 1773. The tea duty was nominal—three pennies on a pound. (It would be interesting to measure this against

the 6.25% sales tax Massachusetts currently levies on its citizens.) Furthermore, the tea, which was surplus tea of the

East India Company, was offered to colonists at half the price Englishmen paid for it.

In fact, the tea was so cheap that it was underselling the Dutch tea John Hancock’s ships were smuggling in. In the

Boston Tea Party of December 1773, of course, the Sons of Liberty, after being customarily liquored up, hurled hundreds

of chests of English tea into Boston Harbor. From Hancock’s perspective, this was largely cutthroat business tactics:

to maximize your profits, destroy your competitor’s merchandise. Although I have friends in today’s “Tea Party”

movement, I regret that its name is fashioned after an act of vandalism. This is our inheritance from Sam Adams, who,

by semantics, transformed criminal deeds into patriotic ones.

While Hancock had an ulterior motive of profit in the Boston Tea Party, Adams’s motive was to push the nation toward

revolution. The dependable Paul Revere was dispatched to New York and Philadelphia with the news. Moreover, the

incident was bound to push England into reacting, as had been the strategy of the Boston Massacre—to, as Adams liked

to phrase it, “Put your enemy in the wrong.”

The “Tea Party” sparked outrage in Britain. Parliament, feeling that they tolerated enough from Boston, ordered the

port closed until the damage was paid for. General Thomas Gage was sent as military governor.

This played right into Sam Adams’s hands. Many in Massachusetts wanted the East India Company compensated, but Adams

blocked every move to pay for the tea.13 The prolonged port

closure brought Boston commerce to a standstill, inciting sympathy for the city in the other colonies.

A reading of British newspapers and speeches in Parliament reveals that Britain considered Boston the source of more

trouble than all the other colonies combined. But characteristically, Adams projected the measures, aimed solely at

Boston, as aimed at all colonies. In a letter to the Philadelphia Committee of Correspondence, he wrote:

|

This attack, though made immediately upon us, is doubtless designed for every other colony, who will not surrender

their sacred Rights & Liberties into the Hands of an infamous Ministry. Now therefore is the Time, when ALL should

be united in opposition to this Violation of the Liberties of ALL.14

|

First Continental Congress

As Miller notes, “No American patriot had demanded more vigorously than Sam Adams a Continental Congress to unite

colonial opposition to Great Britain.”15 The First Continental Congress met in

Philadelphia in 1774, and into this city Sam Adams brought his Boston brand of politics. Quoting Hallahan:

|

Sam Adams’s first step on arriving at Philadelphia was to visit the docks and piers of the riverfront with a local

politician, Charles Thomson, who liked to describe himself as the Sam Adams of Philadelphia. Adams spent some time

on the docks and in the taverns talking with the workingmen there, pressing the flesh and preaching his incendiary

politics. He quickly won many converts—and lined up some muscle.16

|

Although Joseph Galloway, moderate delegate from Pennsylvania, had proposed the Pennsylvania State House as the venue

for the convention

|

Sam Adams pressed for meeting in the smaller, somewhat cramped quarters of the more populist, recently built Carpenter’s

Hall because the workingmen of the city identified with it…. Galloway noted that it was no coincidence that workingmen

from the docks were loitering on the grounds around Carpenter’s Hall in an intimidating

manner.17

|

Sam Adams ran Carpenter’s Hall much like he did Faneuil Hall, doing back-room politicking before actual votes.

Through such machinations, he had himself made temporary secretary of the convention, then Thomson permanent secretary.

Meanwhile back in Boston, by prearrangement, Adams’s lieutenant Joseph Warren hosted a meeting of radicals at Faneuil

Hall; they passed a resolution called the “Suffolk Resolves” (Suffolk is Boston’s county). The resolves called for

a boycott of all British goods, for all towns to raise militias, and for “the inhabitants of those towns and districts,

who are qualified, to use their utmost diligence to acquaint themselves with the art of war as soon as possible, and …

appear under arms at least once every week.” This was a radical step toward war. Warren then dispatched Paul Revere—as

he would on the “Midnight Ride”—to Philadelphia with a copy of the resolves, which the Continental Congress officially

endorsed.

Joseph Galloway, leader of the moderates, proposed a plan of reconciliation with Great Britain. Later, a gallows

noose was delivered to his door, and the next night a message that read: “Hang yourself or we will do it for you.”

Galloway said he lived “in the utmost danger from the mobs raised by Mr. Adams of being hung at my own door.”

|

Every night I expected would be my last. Men were excited by persons northward [Boston], by falsehoods fabricated for

the purpose, to put me to death. Several attempts were made.18

|

Sam Adams’s climactic maneuver at the Continental Congress was procuring a pledge from the delegates that, should

armed conflict erupt between Massachusetts and British troops, the other colonies would come to the aid of Massachusetts.

However, the delegates, distrustful of Adams, attached an important condition to this pledge. They would only help

Massachusetts if the British fired first. When Sam Adams returned home, he had one paramount goal: to produce just

such an incident.

Lexington Coming

However, all during the winter of 1774-75, General Thomas Gage, commander of British forces in Boston, gave Adams no

opportunity. As political flames raged, loyalists sought refuge in Boston, while many rebels evacuated the city.

Boston became a loyalist stronghold, surrounded by a sea of hostile patriots, and Gage had no desire to venture his

troops against the increasingly prepared—and mandatory— “minutemen” militias.

In April 1775, the Second Continental Congress—at which Hancock would preside as president—was due to begin the

following month. Sam Adams desperately needed a “British fired first” incident to bring before the Congress.

Otherwise, the passion for revolution might wane, the moderates would prevail, and there would be no war.

At this juncture, what Hallahan calls “bait” was offered to lure Gage out. Adams and Hancock had been attending

the Massachusetts Provincial Congress (the colony’s provisional independent government) in Concord. General Gage

began receiving intelligence reports that large amounts of munitions, including cannons, were stored in Concord

for an army the Provincial Congress planned to raise. Some of the reports exaggerated the quantity of munitions.

A number of Gage’s reports came from Benjamin Church, the notorious double agent whose true loyalties have long

been controversial.

Gage now made the fateful decision to send troops to neutralize the Concord munitions before they could be deployed

against his own forces. En route, they would have a “date with destiny” at Lexington.

Can it only be coincidence that, on the night before the battle, Adams, Hancock and Revere—the apparent mastermind

and leading propagandists of the “Boston Massacre”—were congregating in a house a few hundred feet behind Lexington

Green? (The house, still standing, is called the

Hancock-Clarke House.)

It was owned by Reverend Jonas Clarke, Lexington’s firebrand patriot-preacher whose wife was Hancock’s cousin.

It has been traditionally reported that Revere rode to the house to warn Adams and Hancock that the British forces

might be on a mission to arrest them. However, although England had authorized Gage to apprehend revolutionary

leaders, including the famous pair, evidence repudiates that this was Gage’s intention that day:

(1) Gage’s

orders to Lieutenant Colonel Smith, who commanded the expedition, only discuss securing the Concord

munitions, and make no mention of arrests;

(2) A force of 700 foot soldiers would be an extremely inefficient instrument for performing an arrest;

(3) In Lexington, the British made no movements toward the Hancock-Clarke House;

(4) After his initial meeting with Adams and Hancock, Revere rode on toward Concord, but was captured by an advance

British patrol at 1 AM. The British knew they had Adams’s famed lieutenant Paul Revere in their hands—but eventually

turned him loose. Had they truly been after Adams and Hancock, they should have held on to Revere, for no one would

better know their whereabouts. (After being released, Revere rejoined Adams and Hancock in Lexington.)

If, in fact, Adams and Hancock were worried about arrest by the British, they displayed little alarm, tarrying at

the house long after Revere’s warning. Furthermore, examination of a letter written by Hancock has revealed they

had already received intelligence about the British movements at 9PM on the 18th—a full three hours before Revere’s

arrival. See the New York Times article

"Letter Deepens Doubt on Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Revere’s 1775

deposition,

describing his midnight ride, makes little mention of alarming the countryside, or shouting

that the regulars were coming, as is famously ascribed to him. He very probably did so, and he certainly discussed

it in his postwar account many years later, but in the original deposition he emphasizes going straight from Joseph

Warren to see Adams and Hancock—this, apparently, was his foremost objective.

In the wee hours of the morning of the 19th, Adams, Hancock and Clarke walked down to Lexington Green and had a

discussion with the militia that had gathered at Buckman’s Tavern in response to the town’s alarm bells. Half a century

ago, historian Arthur B. Tourtellot wrote:

|

Adams and Clarke unquestionably made up a policy between themselves. Adams knew the broad strategy of the resistance,

because he was at this point its sole architect. Clarke knew the men of Lexington and, what is more, could control them

as no outsider could. The policy determined upon between the time of Revere’s first alarm and of the minutemen’s first

muster and the time of the actual arrival of the British troops, was for the minutemen, however outnumbered, to make a

conspicuous stand but not to fire.19

|

The conversation between Adams, Hancock, Clarke and the militia at Buckman’s Tavern has never been revealed, but we know that:

• Adams urgently needed a “British fired first” incident to bring to the upcoming Continental Congress.

• Adams had famously said, “Put your enemy in the wrong, and keep him so, is a wise maxim in politics, as well as in war.”

• Adams had evidently orchestrated the “Boston Massacre.”

Boston Massacre/Lexington Massacre

Indeed, the Lexington affair was sometimes styled the “Lexington Massacre,” and uncanny parallels exist between the two events:

• Prints of each were made. Compare Revere’s notorious misrepresentation of the Boston Massacre to Doolittle’s depiction of Lexington:

|

In each picture, the colonists, who offer no provocation, are being slaughtered by a synchronous, orderly volley from redcoats

upon an officer’s command. This in spite of British reports that shooting at both incidents was sporadic and not in response to orders.

You might recall the words of John Wilson, a deponent, regarding the Boston Massacre:

"Some small boys coming up made a noise to the soldiers, on which the officer said to them why don't you fire? Damn you,

fire ! They hereupon fired."

|

Now look at the words of William Draper, a deponent regarding the battle of Lexington:

|

"The commanding officer of said troops (as I took him) gave the command to the troops, fire, damn you fire, and

immediately they fired."

|

Two separate incidents five years apart, two different officers. Was it standard practice for British officers to instruct their men

to shoot with the words, “Fire, damn you, fire”? One gets the impression that these depositions were scripted by the same writer.

• Indeed, depositions were another common denominator to both events—collected, widely published, and claiming the colonists offered

no provocation whatsoever. But as we have also seen, for the Boston Massacre, these claims did not stand up in court. In the case

of the “Lexington Massacre,” Adams knew the depositions would not be tested by cross-examination, since war had commenced and there

would be no trial. However, the Lexington depositions received their own taint 50 years later, when town pride demanded new depositions

amending the first ones. (At that point, Sam Adams was long dead and no one feared his vengeance.)

• Both incidents were followed by intense communications with neighboring communities via dispatch riders. For the latter event,

the History of the Town of Lexington notes:

|

The report of the bloody transaction at Lexington spread as on the wings of wind, and the fact that the regulars had fired upon and

killed several citizens was known not only in the neighboring towns, but to the distance of forty or fifty miles in the course of the

forenoon. The people immediately flew to arms…20

|

Other colonies were also rallied to arms by reports of the Lexington “massacre” from dispatch riders traversing the coast.

• Both incidents were the subject of vitriolic, dishonest depictions of the British troops’ behavior. Do you recall Hancock’s

florid language in his Boston Massacre oration, and Adams’s claim that soldiers were regularly raping Boston ladies? Now let’s

examine more closely the widely distributed report of Lexington, in the newspaper the Massachusetts Spy. Bear in mind that the

newspaper’s publisher, Isaiah Thomas, met with Adams and Hancock in Worcester, Massachusetts, before printing this:

|

Americans! forever bear in mind the BATTLE of LEXINGTON! where British Troops, unmolested and unprovoked wantonly, and in a most

inhuman manner fired upon and killed a number of our countrymen, then robbed them of their provisions, ransacked, plundered and

burnt their houses! nor could the tears of defenseless women, some of whom were in the pains of childbirth, the cries of helpless

babes, nor the prayers of old age, confined to beds of sickness, appease their thirst for blood!—or divert them from the DESIGN

of MURDER and ROBBERY!...It is noticed they fired upon our people as they were dispersing, agreeable to their command, and that

we did not even return the fire. Eight of our men were killed and nine wounded; The troops then laughed, and damned the Yankees.

|

The report speaks of “defenseless women, some of whom were in the pains of childbirth.” It is true that, during the bloody retreat

back to Boston, the British burned a number of houses, especially those from which they were fired on. However, no historian has

ever found a case where a woman in childbirth was in any way molested. The closest instance was Hannah Adams, who had an 18-day-old

baby, and was forced to evacuate her home. Hannah was not injured, nor the child, who grew up and was herself

married.21

As for those in “old age,” again, there is no known case except 79-year-old Samuel Whittemore. When the British were retreating

through the town of Menotomy, Whittemore, a feisty old war veteran, fired at them from behind a stone wall with a musket and

pistols—killing two redcoats and mortally wounding another. The British troops furiously shot and bayoneted him. Obviously one

cannot plead “old age” when bearing arms, and clearly he was not, as the Spy put it, “confined to a bed of sickness.” Whittemore

survived and died at 97 of natural causes.22

The Hannah Adams/Whittemore incidents were inflated by the Massachusetts Spy into countless assaults upon the gentler sex and

elderly. People reading the broadsides in other colonies had no way of knowing these tales were false. This helped establish a

pattern—for the last two centuries, Americans have been provoked to war by fabricated atrocity stories spun in the press. In the

Spanish-American War, it was Spaniards throwing Cubans to sharks and roasting Cuban priests; in World War I it was German soldiers

bayoneting Belgian babies; in the 1991 Gulf War it was Iraqi soldiers throwing Kuwaiti babies out of incubators. Small wonder

that Thomas Jefferson, himself later victimized by newspaper smears, wrote:

|

Nothing can be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle.

The real extent of this state of misinformation is known only to those who are in situations to confront facts within their

knowledge with the lies of the day.23

|

Oddities at Lexington Green

What really did happen in Lexington on April 19, 1775? My patriot lecturer friend had told me the militia would not have fired

first, because they were outnumbered ten-to-one. But this begs another question: if hopelessly outnumbered, why stand on the

green in the first place?

The Lexington militia behaved very distinctly from other militias that day. When the British reached Concord, the militia there

wisely withdrew to the safety of a hill, then waited until strong reinforcements arrived from other towns. And all through

the day, as the British retreated to Boston, the militias attacked, but from behind trees, walls, and house windows.

How different was the Lexington militia! They stood on an open green, holding their rifles in formation. Did this not invite

confrontation? The redcoats could obviously not march past a hostile armed force on their flank, or leave it threatening their

rear.

Adams and Hancock, who conferred with the militia before the incident, were the two most powerful figures in Massachusetts

(after the war, Hancock became the state’s governor, with Adams his lieutenant governor). The Lexington militia was under the

immediate command of Captain John Parker, an old French and Indian War scout. However, all Massachusetts militias fell under

the authority of the Provincial Congress, of which Hancock was president, and the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, of which

Hancock was chairman. And since Hancock had already had several uniforms tailored for his self-envisioned role as commander

of the entire Continental Army, he would hardly demur at giving orders to a local militia captain.

Although Adams and Hancock retreated to neighboring Woburn before the shooting began, Paul Revere himself was at the green

when the redcoats marched in. This bears comment.

Supposedly, Revere went to the green with Hancock’s clerk John Lowell (yet another Freemason from Boston’s St. Andrew’s Lodge),

because Hancock had forgotten that he had stored, at Buckman’s Tavern, a heavy trunk containing important documents he feared

the British would discover. This means Revere was mingling with the Lexington militia, who were also at Buckman’s Tavern,

until the moment the British arrived, when, he said, he and Lowell then hurried along with the trunk on foot.

While this story may be entirely true, it presents peculiarities:

• Hancock himself had already been to Buckman’s Tavern that morning. If the trunk was so vital, one would think he would

have remembered it then.

• It seems an unlikely concern that the British would have diverted from their expedition to search Buckman’s Tavern, which

of course they didn’t.

• It seems strange that Hancock did not send his coach for the trunk, which could have spirited it away expeditiously.

Surely having Revere and Lowell haul it on foot posed greater danger of its apprehension by the British.

• In case anyone thinks Hancock couldn’t risk sending his gilded coach back to Lexington—he did send it back, famously,

to the Hancock-Clarke house, to fetch a salmon he wished for his breakfast. While Hancock was enough of a fop for such a

vain stunt on the morning that a war was beginning, it begs the question of why he sent the carriage for the salmon,

but not the all-important trunk.

The Shot(s) Heard Round the World

Early in this article, we listed reasons why British accounts of Lexington are more credible than American ones. So let’s

reconstruct the event based on their reports. Bear in mind that the British were already under strict orders not to fire

unless fired upon.

Lieutenant William Sutherland and Lieutenant Jesse Adair were riding ahead of the marching column. As they approached

Lexington village, they heard shots to their left and right, but hearing no balls whistling, assumed it was a local

alarm signal. Then they then saw a colonist aim his musket at them and pull the trigger—but it “flashed in the pan”;

that is, the primer powder failed to ignite the charge in the musket.

Sutherland and Adair rode back and reported this incident to Major John Pitcairn, commander of the lead column. Pitcairn,

who had already heard warnings along the road that a hostile force was waiting at Lexington, now told his troops to load

their guns and fix bayonets. He then ordered them to advance, but not to fire under any circumstances without orders.

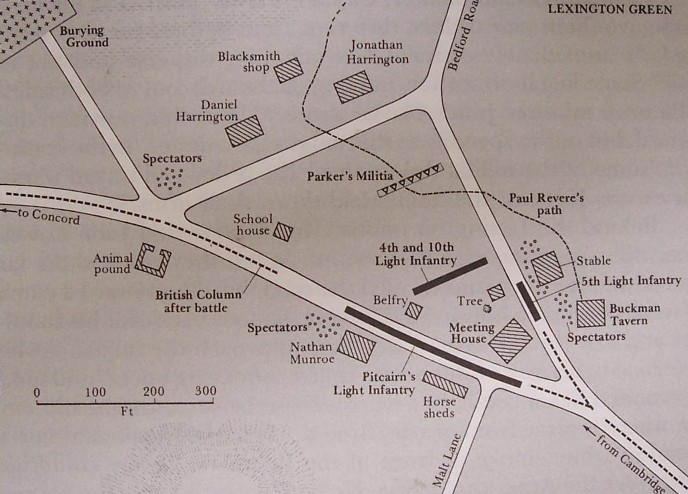

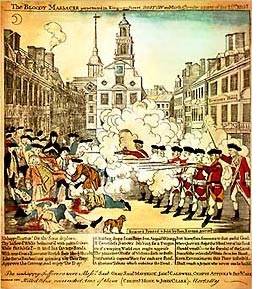

Here is a map of the disposition of the Lexington battle.

|

When the British troops spotted the militia on the green, they split left and right to flank them. At this point, the

first shots at the green itself were fired. Quoting Lieutenant Sutherland:

|

We still went on further when 3 shot more were fired at us, which we did not return, & this is sacred truth as I hope

for mercy These 3 shots were fired from the corner of a large house to the right of the

Church.24

|

The house Sutherland referred to is Buckman’s Tavern. (The “church” and the “meeting house” on the map are one and the

same.) Since there were, of course, no repeating rifles then, this means three shooters. The first of these shots might

technically be the “shot heard round the world.” But though the militias were noted for their marksmanship, all three

shooters missed their targets.

Ignoring the shots, the British kept focused on the militia on the green. Major Pitcairn rode up toward them, and

ordered them to throw down their guns and disperse. At this point, both British and American accounts concur that

the militia began dispersing. However, according to the British, four or five of the militia suddenly dove behind

a wall and fired:

Major Pictairn: “some of the rebels who had jumped over the wall, fired four or five shots at the soldiers.”

Lieutenant Sutherland: “instantly some of the villains who got over a hedge [wall] fired at us which our men for the

first time returned.” Ensign Jeremy Lister, writing an account several years later, reversed the sequence and said:

“they gave a fire then run off to get behind a wall.” Since Pitcairn’s and Sutherland’s accounts were written shortly

after the event, they can be assumed more chronologically accurate. Pitcairn’s report also noted that his horse was

hit by shots fired from “some quarter or other” and “at the same time several shots were fired from a Meeting House

on our left.”25

(I would like to interject here that Major Pitcairn, who later died at Bunker Hill, was not a man to whitewash a report;

he was widely known for his integrity and courage, such that even the Sons of Liberty paid him respect, a high compliment

indeed.)

So, not counting the “flash in the pan,” we have three shots from Buckman’s Tavern, four or five shots by the men

who jumped behind the wall, perhaps more from “some quarter or other,” and “several” from the meeting house. Based

on the British reports, it appears that upwards of ten shots were fired on the redcoats before they returned fire.

According to all British accounts, their return fire was not based on orders given, but was a spontaneous, disorderly

reaction to the multiple shots the Americans fired. The green now billowed with musket smoke, and the British officers

had to restrain their men with considerable difficulty.

The three men who fired from the corner of Buckman’s Tavern surely knew they were jeopardizing the militia on the

green. So must have the men who jumped the wall. It is noteworthy that Paul Revere—whose alarm brought the militia

out in the first place—had been at Buckman’s Tavern only moments before the “shot heard round the world” was fired from

that very place. The map details Revere’s path, which took him from Buckman’s right through the militia. Was he really

there just to haul a trunk, or was he choreographing the incident, passing instructions as he moved along?

Of course, I don’t believe for a moment that the Lexington militiamen were planning to sacrifice themselves as cannon

fodder, any more than the mob at the “Boston Massacre.” I suggest that only a few were “in the know”—the individuals

who fired the opening rounds from protected places, leaving the men on the green to absorb the fury of British

retaliation.

But is there any evidence that there was a group separate from the Lexington militia? There is. Later in the day,

as the redcoats were retreating from Concord, General Gage sent a relief column from Boston under Brigadier Hugh Percy.

Riding as a scout for Percy’s column was an American loyalist, George Leonard. His statement is among General Gage’s

papers:

George Leonard of Boston deposes that he went from Boston on the nineteenth of April with the Brigade commanded by Lord

Percy upon their march to Lexington. That being on horseback and having no connexion with the army, he several times

went forward of the Brigade, in one of which excursions he met with a countryman [American] who was wounded supported

by two others who were armed. This was about a mile on this side of Lexington Meeting House. The deponent asked the

wounded person what was the matter with him. He answered that the Regulars had shot him. The Deponent then asked what

provoked them to do it—he said that some of our people fired upon the Regulars, and they fell on us like bull dogs and

killed eight and wounded nineteen. He further said that it was not the Company he belonged to that fired but some of

our Country people that were on the other side of the road. The Deponent enquired of the other men if they were present.

They answered, yes, and related the affair much as the wounded man had done. All three blamed the rashness of their own

people for firing first and said they supposed now the Regulars would kill everybody they met with.

Boston, May 4, 1775

George Leonard 26

|

Note Leonard’s report that the wounded man said “it was not the Company he belonged to that fired but some of our Country

people that were on the other side of the road.” This indicated the Buckman Tavern area, across the street from the green.

It shows that Lexington’s armed men were not one cohesive unit.

The phrase “not the Company he belonged to” adds interest to the wording of the Lexington militia’s depositions. 34

deponents signed a statement declaring that “not a gun was fired by any person in our company on the regulars to our

knowledge before they fired on us.” Another 14 signed a statement that “the regulars fired on the company before a gun

was fired by any of our company on them.” (Emphasis added.) These statements don’t exclude the first shots being fired

by Americans—rather, they deny any such shots came from “our company.” This nuance may have been important in persuading

some militiamen to sign the collective depositions. If anyone’s conscience gave him pause, men like Reverend Clarke

could always assure him that the statement was, technically, true; and that one’s patriotic duty to avenge the dead

outweighed considerations over exactness.

Who were these gunmen who fired the opening shots from protected places? It seems highly doubtful that they were members

of the Lexington militia, who would not have willfully endangered their friends and kinsmen. Of course, some shots came

from the four or five men who, having been on the green, jumped a wall and fired; but not every man that had assembled on

the green was from Lexington; some told Parker they had come from neighboring districts, having heard the town’s bells

tolling. William Draper (who signed the deposition saying the British officer cried “Fire, damn you, fire!”) stated

that he was on the green with the Lexington militia, yet gave his residence as the faraway town of Colrain.

Is it possible that John Lowell was not the only Freemason from St. Andrew’s Lodge whom Revere brought to the green shortly

before the British arrived? A number of Sam Adams’s “Mohawks” had fled Boston after its loyalist consolidation and would

have been at large that April. Was the “Boston Massacre” strategy being replayed?

Though I will doubtlessly be accused of gross speculation, I would like to know a better reason why, with the militia

hopelessly outnumbered, a few men fired on the redcoats from concealed locations, leaving the militia on the green to bear

the consequences. And I would also like to hear why the town of Lexington kept its firing—of shots of any kind—essentially

a secret for fifty years.

I now offer further speculation. You will recall that when lieutenants Sutherland and Adair, riding in advance, approached

the green, they saw a colonist aim his musket and pull the trigger, but the powder “flashed in the pan.” The officers

thought they had been spared by a lucky “misfire.”

Then we have three shots from Buckman’s Tavern that all missed. And with the shots from the wall and the meeting house,

and any in the subsequent exchange, the British suffered only one wound; none were killed. This is quite a contrast to

the rest of the day, when the redcoats suffered some 250 casualties. Remember, even 79-year old Samuel Whittemore killed

three redcoats firing from behind a wall. Yet the Lexington men, with a multitude of shots from various locations, couldn’t

inflict one significant hit on the troops amassed before them.

Perhaps there were no British dead at Lexington Green because Adams and Hancock wanted none. If redcoats had to be buried

in the village, it might have cast doubt on the tale of an “unprovoked massacre.” I suggest that some shooters may have

missed on purpose, perhaps even firing “without ball.” Perhaps the “flash in the pan” was not a misfire but an attempt

to provoke without drawing blood.

What the British marched into was a trap. No matter the precise details, the outcome was virtually guaranteed:

• The militia standing in battle formation guaranteed the redcoats would confront it.

• Firing shot after shot at the British guaranteed that at some point a threshold would be reached, and the redcoats

would fire reciprocally—very parallel to the “Boston Massacre,” where soldiers were pelted and clubbed to the point

of shooting in self-defense.

• Firing but deliberately missing guaranteed the British would experience few if any casualties; there would be high

colonist casualties by comparison. Thus statistics would corroborate the “Lexington massacre” story.

Perhaps John Adams’s comment on the Boston Massacre bears repeating here: “I suspected that this was the explosion

which had been intentionally wrought up by designing men who knew what they were aiming at, better than the instruments

employed.”

For John Hancock, the battle of Lexington, like the Boston Tea Party, was profitable; with the outbreak of war, some

500 smuggling indictments, pending against him in the courts, vanished.27

But for Sam Adams,

the picture was much broader. Upon hearing the distant Lexington gunfire, he turned to Hancock and famously said,

“What a glorious morning is this!”

As historian William Hallahan put it, “For the price of a few dead farmers, Adams could buy his

war.”28

Afterword

Before concluding this article, there are two corollary issues I should address.

One is Sam Adams’s character. He is obviously “the villain of my piece.” Am I obsessed with hating him? Have I nothing

good to say of the man?

To Adams’s credit, he was not, like Hancock, a materialist. He lived a simple, frugal lifestyle, and did not seek

riches from his revolutionary agitations.

In fact, it has been said that he sought to emulate his Puritan forefathers. He prayed, read the Bible, and, after

the war, even publicly opposed amusements such as clubs for card-playing. However, to oppose card-playing, while

suborning mob violence and property destruction, and habitually engaging in “ends justify the means” lying and slander,

is to mis-prioritize virtues, a practice that Jesus Christ condemned the Pharisees for.

To his credit, Adams opposed centralization of government under the Constitution unless amendments (i.e., the Bill of

Rights) were appended. Yet many found Adams’s postwar views on liberty self-contradictory. For example, when rural

Massachusetts farmers and veterans, finding their property confiscated for inability to pay state taxes and debts,

began what was known as “Shay’s Rebellion,” Sam Adams (then president of the Massachusetts senate) called the rebels

“traitors,” declared that their leaders should be executed (two were hung), and helped push through a senate bill

suspending the right of habeas corpus during the crisis.

But my article raises a more significant issue. It has concluded that the Massachusetts events, used to spark

the Revolutionary War, were predominantly specious. What, then, does that say about the war itself, the American

nation it spawned, and the Founding Fathers in general?

I have been asked to be a public speaker on many occasions by patriotic groups who honor the Founding Fathers and

strive to uphold the U.S. Constitution. I consider members of these groups to comprise the core of our best citizens

in America.

Furthermore, the Bill of Rights is an unparalleled charter of freedoms—concise, eloquent, and so long as upheld,

a bulwark against totalitarianism. I appreciate having the freedom to write this article.

However, contrary to popular belief, most of these freedoms were not denied to 18th century colonists by Great

Britain. Freedom of religion? No redcoats forced people to attend particular churches at bayonet point. Freedom

of speech? No redcoats sat in homes or taverns, telling people at gunpoint what they could or couldn’t say.

It may justly be said that the Bill of Rights was spurred as much by Americans’ distrust of each other as by any

harsh experiences with Britain. This is not to dispute, of course, that British customs officials sometimes carried

out warrantless searches, or that colonists, while enjoying the right to jury trials, were sometimes subject to

British admiralty courts. But as Paul Noble points out, Americans were not being denied “life, liberty and the

pursuit of happiness” before those words were penned.

The principle grievances with England centered around taxes. In retrospect, removed from the passions of that

era, Britain’s desire to have America share the burden of paying for the French and Indian War does not seem very

unreasonable (though it must be conceded that the colonies had borne high costs of their own during that conflict).

To meet the expenses of administration and defense, every government must raise revenues. To do so, it must lay taxes;

if not taxes, customs duties. It may also, of course, borrow; but what it borrows must be repaid later with interest.

The British attempted to tax America; when this was rejected, it tried customs duties. Parliament’s willingness to

successively repeal, in response to American objections, the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend Acts,

reveals a conciliatory flexibility, rather than intractable tyranny. When America won the Revolutionary War, she

immediately began raising revenues by levying her own taxes and customs duties. The U.S. Customs Service was

established in 1789. There is no free lunch.

I realize that the chief distinction made was “taxation without representation,” so let’s explore that. First,

the colonists did have degrees of representation—they had their own legislative assemblies, which could present

grievances to the royal governors. The colonies also had agents in England to lobby Parliament. Benjamin Franklin

was the most famous of these.

So the dispute boiled down to the colonies not having voting representatives in Parliament. But how practical would

that be? Let us say the colonial assemblies selected representatives to serve in Parliament. In those days of sailing

ships, a transatlantic trip could easily take two months or more. Now suppose, after arriving in Parliament, the

American representatives were confronted with a tax proposal. If they wished to sound out their home colonies,

they would have to return to America by ship (or send a messenger or letter), consuming another two months—of course,

no phones or email back then. The colonial legislatures would then have to reconvene to consider the proposal.

Then the representative would have to sail back to Britain—another two months. With representatives arriving from

different colonies at different times, one begins to sense what an impractical way to conduct Parliamentary business

this would have been.

Furthermore, Britain then being more populous than the colonies, America would probably have been outvoted on tax

measures anyway—making the representation issue rather moot in its practical outcome.

I have written on the

Holodomor, in which Joseph Stalin subjugated the Ukraine by murdering millions through enforced

famine. To me, that is tyranny and slavery. To call a three-cent tax on a pound of tea “tyranny” and “slavery” (or

as Sam Adams liked to put it, abject slavery) is pale by comparison.

I do not deny that the colonists had other grievances, or that the levied taxes would have been a hardship to

some, or that corruption existed on the British side of the scale. But I think it unfortunate that so many American

patriots regard the Founding Fathers as having stature bordering on sainthood. This has shielded them from candid

scrutiny.

I recommend that interested readers see the film (viewable on YouTube)

Hidden Faith of the Founding Fathers. Though

quite long, and I do disagree with aspects of the film, it is a welcome balance to the works of men like David Barton,

who have overdrawn the Fathers as heroes of the Christian Faith.

As a Christian myself, aspects of the American Revolution had troubled me long before researching this article.

When asked about taxes, Jesus said “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.” He didn’t say, “You don’t have to

pay because you don’t have representation in the Roman senate.” The Bible also prescribes obedience to authority

(Romans 13:1-2) except in the case of choosing between God and men (Acts 5:29). I have often heard Christians

quote scriptures on paying taxes and the virtues of obedience to authority; yet the Founding Fathers somehow always

get a “free pass” on these standards.

Rebelliousness has never been a companion of good character. In families it has begotten brats, in politics Bolsheviks.

Satan staged a rebellion of his own in heaven.

Some may accuse me of being an “anglophile” for writing this article. But—other than enjoying old comedies with Peter

Sellers and Alec Guinness—I plead innocent. I have never visited the UK, and no British blood flows in my veins. I

have no motive other than seeking truth—and I am not seeking to bring America back under British dominion. In point

of fact, an Anglo-American political alliance, nurtured by banks and multinationals, has been in effect for over a

century, and anyone familiar with my other writings knows how critical I have been of those interests.

Finally, as an American, I will be accused by a few of being unpatriotic, perhaps even treasonably so. I would

like to answer that charge in advance.

I have lived nearly all my life in and around Boston. As is well known, Bostonians have a near-fanatical love of

their baseball team, the Red Sox, a passion matched only by their hatred for the team’s nemesis, the New York Yankees.

At a sporting event, it is OK, if one wants, to imagine that the home team consists only of angelic heroes, while

all the other club’s players personify evil.

But history is not a game, nor is war. Patriotism is a virtue, that is true. But truth is also a virtue. Of these

two virtues, which is higher? Which is numbered in the Ten Commandments?

Where does my patriotism end? It ends where it asks me to forsake the truth.

I thank Paul Noble for enlightening me to British perspectives on the Revolutionary War, and for graciously posting

this article on his website.

***James Perloff is author of several books, including Truth Is a Lonely Warrior, published this year in both

Kindle

and

paperbound editions. It discusses many other suppressed stories of American and world history.***

NOTES

1. William Heath, Memoirs of Major-General Heath, (1798; reprint, New York: William Abbatt, 1901), 5-6.

2. Vicomte Léon De Poncins, Freemasonry and Judaism: Secret Powers behind Revolution (1929, reprint; Brooklyn, N.Y.: A & B Publishers Group, 1994), 33-34.

3. Les Standiford, Desperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals who Led the Colonies to War (New York: HarperCollins, 2012), 35.

4. William H. Hallahan, The Day the American Revolution Began: 19 April 1775 (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 234.

5. John C. Miller, Sam Adams: Pioneer in Propaganda (1936, reprint; Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1966), 239.

6. Ibid., 267.

7. Harold Murdock, The Nineteenth of April 1775 (1923, reprint; Cranbury, N. J.: The Scholar’s Bookshelf, 2005), 18-19.

8. Miller, 175.

9. A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston (Boston: Edes & Gill, 1770).

10. Miller, 189.

11. Paul M. Zall, ed., Adams on Adams (Lexington, Kent.: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 38.

12. Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 1 (London: British and Foreign Public Library, 1818), xxxv-xxxvi.

13. Hallahan, 54.

14. Standiford, 220-21.

15. Miller, 306-7.

16. Hallahan, 132-33.

17. Ibid., 133.

18. Ibid., 143.

19. Arthur B. Tourtellot, Lexington and Concord: The Beginning of the War of the American Revolution (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1963), 112.

20. Charles Hudson, History of the Town of Lexington, Massachusetts, vol. 1, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913), 155-56.